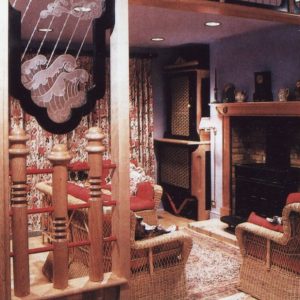

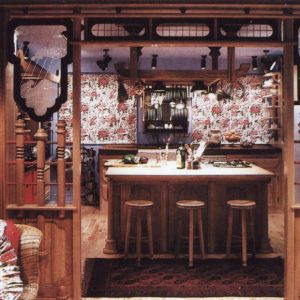

The Newell’s Kitchen, Mark Lewis as Associate for Johnny Grey Designs, 1980-83.

An American couple, the Newell’s, left their former residence of William Morris’ Lemscott Manor in Oxfordshire, to move to London. They wanted to emulate and recreate the quality of environment they had enjoyed in the countryside in their new London home.

Betsy Newell was a passionate cook who taught London society hostesses. George Newell, an entrepreneur, was an expert on fine wine. They enjoyed hosting informal parties for international personalities and statesmen who, whilst sipping aperitifs and discussing issues of the day, were frequently put to work peeling the potatoes! This area had to be suitable to relax, work and dine in. Consequently, they both set very exacting standards for their kitchen.

The materials used comprised of English olive ash, enameled steel, black lacquer, acid etched glass, hand cane work, granite, stainless steel, Persian carpet, brick hearth and oak floors. They were turned, carved, machined, bent and shaped into the precise detail of the furniture elements within this 450sq. ft. basement snug, providing the kitchen that was desired.

Article by Mark Lewis. First appeared as A Good Plan, Spring 2012 Opening Doors magazine (Guy Leonard & Co)

Interior Design Consultant Mark Lewis explores the foundations on which open plan living was based.

For the last 50 years, homeowners have been knocking down interior walls and building extensions to create that open plan look and make better use of the space available.

The Scandinavian approach offered something new and modern – a more minimal design and a change from the style of the 50s and 60s. For the first time, contemporary design ideas were universally embraced and celebrated and were enthusiastically introduced at every social level during the regeneration of post-Second World War society. The origins of the modern approach to living began to emerge in the early 20th century but were interrupted by the First World War with scarcely a moment to breathe before the distraction of the second.

My first personal experience of open plan living was when visiting my Uncle’s house in Surbiton in the late 60s, when I was only 11. He is an architect and at that time worked for the Greater London Council supervising their civic developments, mainly schools and hospitals.

Earlier in his career, after leaving college, he joined the practice that designed most of the features for Festival of Britain in 1951. Not only was he a keen modernist, as many post war architects were, having absorbed the edicts of the Bauhaus and Le Corbusier, but he also met and married a young East German who had escaped the Russians and managed to get into Britain as a refugee. She brought into his life a thoroughly European approach to family living.

Having established a career for himself by then, he set about building a thoroughly modern family house – mostly wood and glass with split levels. A large round dining table sat in the dining hall adjacent to the open kitchen area. It had a revolving disk insert in the centre, which we pushed to pass the amazing selection of pastries and teatime condiments.

Another open plan house I first experienced before I had begun my own design education as an under graduate was a rather modest interpretation of the theme (possibly inspired by those Sunday visits to Surbiton). This was my older brother’s efforts to modernise a small terrace house in Chester – known then as a ‘two-up two-down’ with backyard and privy.

The front room, the ‘parlour’ as it was called by its original occupants, was reserved for when the Padre came to visit or the laying out of the dead. It was the back room that had the fire and hot water kettle, a sink and a table, and one or two fireside bucket chairs, leaving scarcely any room to move about.

This room, used all the time, was the only warm room in the house. This is unless someone was sick and a fire was lit in a bedroom. A lot of enthusiasm with a hammer soon tore out the tight hallway and dividing wall between the two rooms leaving the stairway stringers exposed. By incorporating the ‘privy’ and coalhole situated at the back of the house into the main room, the kitchenette became a new feature, open to the new living and dining area. Furnished with a Futon sofa made of salvaged wood and home sewn and dyed Hessian bean bags, together with a freshly sanded slide leaf table and French cafe chairs, the ensemble completed an interior that was likely one of the earliest Habitat-inspired homes.

Most British residential building stock is over a hundred years old and enjoyed for its charm and distinction. Currently contemporary homes are built on small plots using traditional footprint but modern building techniques. These often lack the integrity associated with original Victorian or Edwardian architecture and represent an inhibited housing initiative of recent governments – a far cry from those of Harold McMillian’s promise to build 300,000 new homes year, who embraced the modern ideas of architects and the ruthless ambitions’ of the developers who set about the task of rebuilding Britain.

We have their legacy. Some of which (the more successful high-rise buildings of the Alton Estate, Roehampton in South West London, and the Barbican development in the City of London) are good examples of post-war architecture and are now highly sought after and modern homes.

As one travels along the copious urban and suburban avenues of 18th and 19th century houses, terraced, double fronted or detached, one could imagine their interiors matching those depicted in period dramas.

What one often finds instead, after further inquiry to the rear, are the extensions and the interior alterations that have made these once intimate cocoons for living into veritable ice-rinks of domestic function. Open plan from entrance door to sliding glass wall panels opening up the rear of the house, there is little or no indication that the back garden is any less or more a significant space than the dining area, or that one is in a different space to the lounge, living room, sitting room – snug it definitely could not be, or whatever words we may now use to describe that space we may have a Sunday afternoon snooze in after lunch. Certainly not the drawing room given that in these houses there are no longer any rooms from which to withdraw.

Other than the occasional depiction in a home magazine of radical interiors which include the bath or wet room-type shower in the bedroom, the upper floors of our houses are less likely to be as open plan as the ground floors.

My own career started in earnest applying the fashion for open plan in the early 80s. My clients were pleased to have me re-model their homes with an emphasis on the kitchen being the prevalent room in the house, which would require the opening up of either the lower ground or the ground floors, presenting a room for cooking and living in as one area incorporating dining, sitting and kitchen in an architecturally cohesive themed room that acknowledged the desire to have the ability to entertain and cook in the same space.

At the time of their last renovation, these homes had adjusted themselves to deal with the lack of domestic staff enjoyed by the previous era’s occupants. To maintain the notion that the food was still prepared by others, the kitchen was more of a utility from which the hostess would emerge with a trolley laden with the warmed serving dished full of food to be issued on to the table after which guests were invited to come into the dining room having had their aperitifs in the living room (more often than not, in the absence of the hostess who had actually done all of the cooking).

The most expert of hostesses would plan the menu to ensure that as little time as possible would be spent away from the gathering of friends and family, and that the logistics of the dining experience did not appear to be too much effort or a distraction from the social occasion.

One of my more extraordinary clients in those early days was an enthusiastic cook of near professional expertise, whose husband, a financier of international projects like building dams in far flung continents around the World, would often entertain senior British politicians and their international counterparts.

The whole orientation of the house was adjusted to create an environment equitable to their expectations of presentation, usually reserved for the reception rooms but now incorporated into the kitchen.

On completion of the refurbishment, and a few dinner partie,s later her eminent guests were reported to have been thrilled and charmed to be able to have helped in the kitchen like any family member, gossiping and chatting about the stuff of life whilst peeling the potatoes and trimming the broccoli.